Please note: This article is the second in our HealthTech - Shifting Landscapes Series. For an introduction to this series, overview of the trends and legal issues in the industry, and information on articles that will follow in this series, please see our first article here.

The Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) market is a nascent market which offers huge growth potential; but there are distinct growing pains.

What is SaMD?

SaMD uses data input to output results which have a medical purpose. Input data may include clinical data (lab results, patient symptoms etc.) or data from wearable devices (wearable HealthTech will be the focus of a later article). The output results are designed to carry out a medical function. This may include informing clinical decision-making or patient health decisions. This is achieved through algorithms, analysis engines and model based logic. Examples include mobile-connected smart thermometers that can track and share health status (including with a healthcare professional) and even recommend and deliver reminders to take medication (including dosage); software that helps radiologists and clinicians find and diagnose a cardiovascular condition by analysing MRI scans; or a dedicated piece of software that monitors a mole for a given period of time to assess the risk of melanoma.

Advancements in use of Big Data and machine learning (ML) in SaMD algorithms means the potential of SaMD only grows further; but there are distinct growing pains. These include ambiguity around definition of SaMD, lack of and fragmentation of regulation, classification and categorisation within the SaMD market, and complexities around protecting any underlying IP.

Ambiguity in the definition of SaMD

The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) definition of SaMD is:

"software intended to be used for one or more medical purposes that perform these purposes without being part of a hardware medical device." [1]

Demonstrating and/or realising an intended “medical purpose” use is potentially harder to evidence one way or another for software given its intangible and remote nature. Hardware products can physically be seen to be used whereas lack of visibility over SaMD makes the scope of intended use potentially harder to determine.

Once software is confirmed as being used for a medical purpose, the question becomes whether it is a medical device in itself. SaMD does not include software embedded in a medical device to "drive or control" that device or which is an accessory to a medical device or in vitro diagnostic medical device. For example, the software that programs MRI magnets to turn is software in a medical device (SiMD), whereas software that helps radiologists and clinicians find and diagnose a cardiovascular condition by analyzing MRI scans is SaMD. Similarly, software which retrieves information and optimizes processes on an app which is a medical device (such as electronic health records) is an accessory to that medical device, not SaMD. However, software which performs a further action on that information to inform and/or help (directly or via a clinician) to treat or diagnose, is SaMD.

This distinction dictates whether the software is deemed a medical device in its own right (in which case all the relevant, onerous regulatory processes apply) or can be placed on the market on the basis of the associated medical device's conformity assessment. Given the diversity of software used for a medical purpose (in itself or otherwise), determining which category medical device software falls under can be difficult.

Lack of regulation

The legislative framework governing medical devices is fundamentally designed for hardware products. Debate around whether software is a good/product or a service is fraught.[2] Indeed software was only added to the definition of 'products' capable of being a medical device in 2008 under EU legislation (on which many jurisdictions' MD regulation is based). This slow and fragmented acceptance of SaMD in global legislation is illustrated below.

Key characteristics of software incongruous with traditional hardware products and accompanying legislative frameworks include: 1) the remote, non-tangible nature of software; 2) risk of incompatibility; and 3) the fact that software undergoes regular updates.

1. Intangibility

Evidencing efficacy/standards thereof, 'product' faults and attached liability is harder given software's remote nature. Product liability regulation relies on a) evidencing a chain causation between product fault and damage/loss caused, b) establishing whether the resultant damage/loss was foreseeable; and c) identifying adequate precautions to mitigate such damage/loss. These tests are much harder to satisfy when the product and its direct effects are not tangible.

2. Interoperability

Everyone knows of the frustration of purchasing a new phone only to discover the headphone jack or charging port is new and unique to the new model. Interoperability is essential to maintaining a healthy, competitive SaMD market.

3. Frequent updates

Though frustrating at times, regular software updates are essential to maintaining functionality, efficiency and security. Classification and categorisation must be re-evaluated with each iteration/update which impacts the SaMD definition or risk profile at least. Regulating for and ensuring compliance of a static product or even for example a medical product which is improved, is much easier than doing the same for a product which constantly evolves.

Regulation across jurisdictions is disjointed and fragmented, partially as a result of different approaches in attempting to manage these issues and the lag in doing so.

The China Food and Drug Administration makes a distinction between major and minor software updates; major being those that impact medical device safety and effectiveness.[3]

Meanwhile, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published draft guidance last November which emphasises the importance of interoperability and the interoperability-related information manufacturers are required to submit in SaMD premarket submissions and labelling.[4]

Fragmented regulation

Different jurisdictions have different processes for bringing SaMD to market including scope of products caught under the regulation, risk framework and conformity requirements to certify safety. Adopting a tailored regulatory process can accelerate the approval process and improve access to products which meet patient needs specific to the jurisdiction.

Japan's SAKIGAKE Designation System aims to prioritize and accelerate review of novel advanced treatments.[5] This accelerated approvals process is intended to make Japan an attractive location to conduct clinical trials and submit marketing applications for innovative products; an advantage for both Japan and Japanese patients. However, fragmented approaches complicates multi-jurisdictional applications for certification.

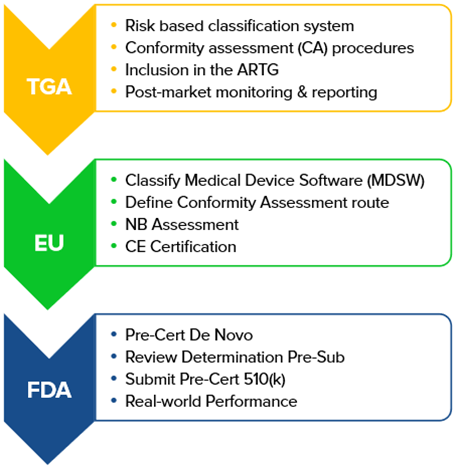

Differing approaches of some major regulatory bodies are illustrated below:

Even within any one jurisdiction, there is generally a 'patchwork' of different pieces of legislation governing different aspects of SaMD. This gives rise to potential for duplication, conflict and misalignment. Within the EU for instance, the categorisation process under the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) and In-Vitro Medical Device Regulation (IVDR) differs and the recent Artificial Intelligence Act seeks to amend them even as they are implemented.

The IMDRF, US FDA and European Commission’s Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) are key driving forces behind guidelines on development and implementation of SaMD including possible framework for risk categorization and application of quality management systems. Regulation is adapting to better accommodate SaMD and encourage reciprocity of certification across jurisdictions.

The majority of medical devices supplied in Australia for instance, rely on the Therapeutic Goods Administration's (TGA’s) acceptance of EU certification and similar provision exists in other jurisdictions. However it remains the case that SaMD does not fit seamlessly into the current legislative frameworks for medical devices. Consultations and review is ongoing with the aim of ensuring medical device regulations capture a sufficient breadth of software to protect patients and public.[6] The lack of and fragmented regulation can be a bottleneck to new product launches if not managed and any changes predicted for properly.

SaMD Categorisation

Classification and categorisation of SaMD is broadly based on (1) Risk to the individual/public health; and (2) significance of SaMD output result to a healthcare situation. Compliance requirements are more onerous the higher the risk to the patient/public and greater the significance of the SaMD in diagnosing/treating/providing therapy to the patient.

Whether SaMD is intended to inform the actions/decisions of a layperson or a healthcare professional will have a profound effect on determining risk/liability matrix. This is acknowledged in the classification process. For instance, Australia's TGA classes SaMD intended to inform a relevant healthcare professional lower than that intended to inform a layperson. Use instructions must be that much more carefully drafted and considered where directed to those without relevant clinical expertise. Conversely, risk of product faults and therefore product liability are highest for SaMD where less human intervention is required.

Correct classification of SaMD ensures the correct level of scrutiny. Failure to comply or mistaken categorisation can be incredibly costly as tests may have to be re-performed, product launched postponed or products recalled.

Intellectual Property protection

Patentability of both software and medical devices individually is particularly complex and differs between jurisdictions; the combination of the two fields exacerbates this.

Some critics propose a system for software patenting similar to that for biological materials i.e. a repository where code must be stored and shared in return for IP rights. In the case of biorepositories, the rationale is that this sharing acts as an incentive to share the invention enabling further study, improvement and development. For software, this would mean that code would be shared but rights therein retained and protected. What IP protection is available will differ on a case by case basis and this grey area will need to be careful navigated.

The SaMD market offers great opportunity - but mind the gaps

In summary, the SaMD market is an incredibly exciting one. Lag in appropriate regulation of software technology is relevant to all sectors, not only HealthTech, and is by no means a barrier to the market. Nevertheless, the fragmentation and complexities addressed above require manufacturers (with the aid of their advisors) to remain up to date and cognisant of the evolving international regulatory environment.

References/Further information:

[1] IMDRF SaMD N10 2013: Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Key Definitions

[2] See most recently the CJEU Case C‑410/19 of The Software Incubator Ltd v Computer Associates (UK) Ltd in which it was held that software is considered a 'good' (and therefore a product - see para 34) for the purposes of the EU's Commercial Agents Directive 86/653/EEC.

[3] “Principle of technical review of medical device software” (2015 Order No. 50)

[4] See draft FDA guidance (which stresses the importance of interoperability) here.

[5] Japan's SAKIGAKE Designation System was established as a permanent system under Japan's Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (PMD-Act).

[6] For example, the UK's Software and AI as a Medical Device Change Programme.

/Passle/596df0e43d947619ec025f26/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-10-08-10-50-28-575-67050e74c71f57809f6d0411.jpg)

/Passle/596df0e43d947619ec025f26/SearchServiceImages/2025-03-17-10-33-28-399-67d7fa78bf14cca0f5e2c402.jpg)

/Passle/596df0e43d947619ec025f26/SearchServiceImages/2025-02-05-11-45-56-829-67a34f74966bf3c993454c6a.jpg)

/Passle/596df0e43d947619ec025f26/MediaLibrary/Document/2025-02-04-16-21-29-274-A27003_Life_Sciences_January_2025_Brochure_English_V1_afterchange_thumbnail_1.png)

/Passle/596df0e43d947619ec025f26/SearchServiceImages/2025-01-24-09-38-32-700-67935f98312d8a93f10c9c08.jpg)